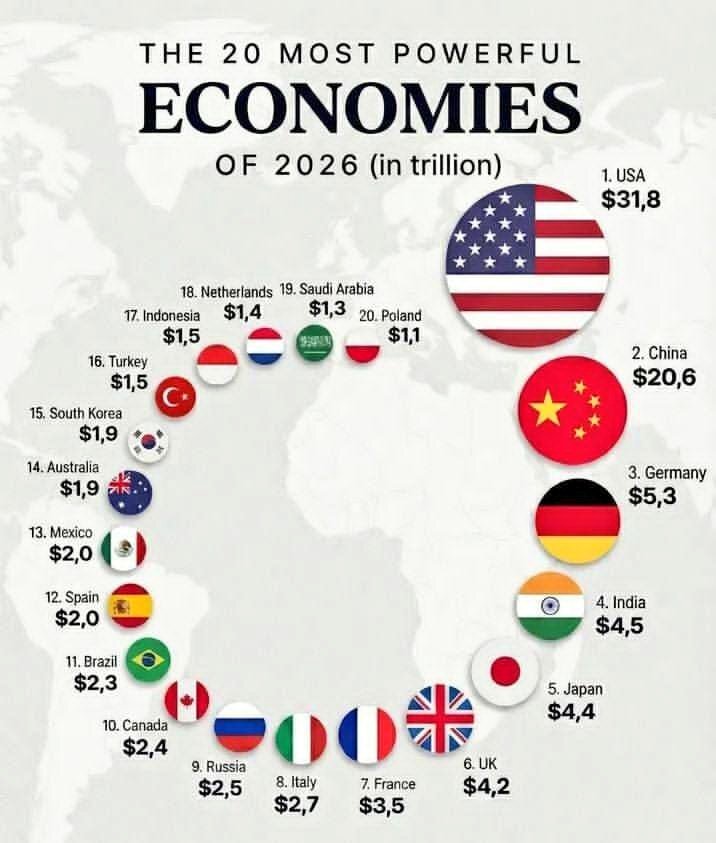

Poland’s Rise into the World’s Top 20 Economies: Geography, Services, and a 25-Year Transformation

Poland’s entry into the Top 20 largest economies in the world marks a historic shift in Europe’s economic landscape. With a nominal GDP of approximately USD 1.1 trillion, Poland has joined a small group of countries that collectively generate over 80% of global GDP.

This milestone is not the result of a short-term boom or a single reform. It reflects a 25-year structural transformation driven by geography, services, productivity, and a uniquely distributed urban growth model.

Why Joining the Global Top 20 Economies Matters

Becoming a Top-20 economy is more than a symbolic ranking. It fundamentally changes how a country is perceived by global investors, corporations, and policymakers.

For Poland, this means:

- greater visibility in global capital allocation,

- stronger influence in international economic discussions,

- higher attractiveness for long-term and strategic investments,

- recognition as a systemically relevant economy, not a peripheral market.

In 2000, Poland’s nominal GDP stood at roughly USD 170 billion. By 2025, it expanded more than six-fold — a scale of growth matched by very few large European economies over the same period.

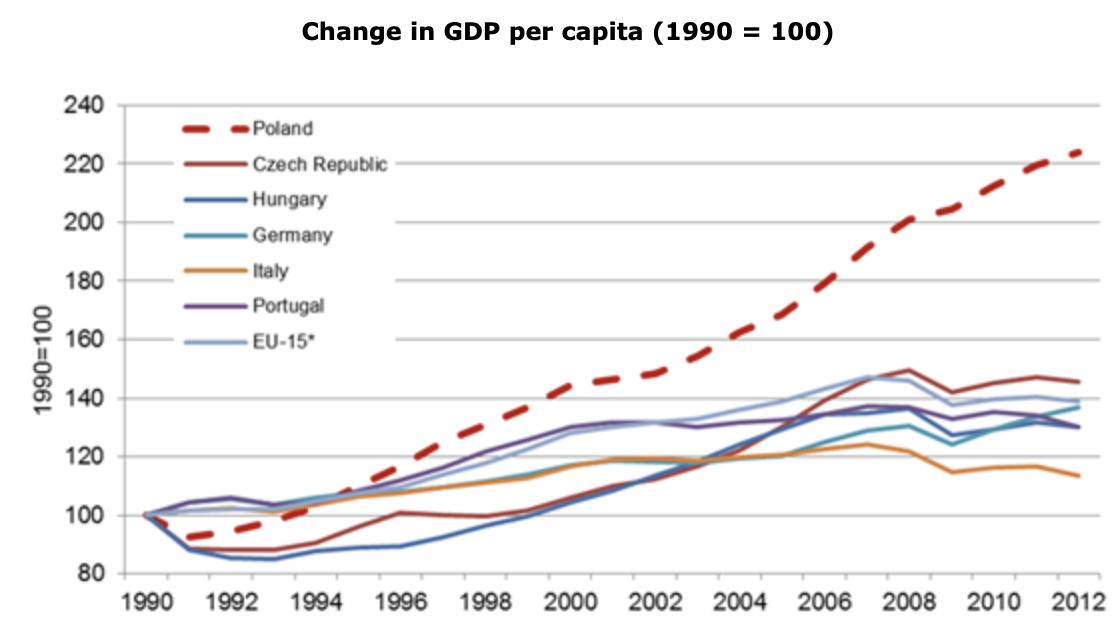

A 25-Year Growth Trajectory That Stands Out in Europe

Poland’s long-term growth performance is exceptional even by Central & Eastern European standards.

Key indicators show:

- GDP growth (2000–2025): +500–600% nominal,

- GDP per capita (PPP) rising from around 50% of the EU average in the early 2000s to over 80% today,

- uninterrupted growth with no recession during the 2008–2009 global financial crisis,

- average real GDP growth among the highest in the European Union over two decades.

According to OECD and World Bank data, Poland is one of Europe’s fastest-converging economies in terms of income and productivity.

Geography as a Strategic Asset, Not a Coincidence

One of the most underestimated drivers of Poland’s rise is geography used strategically.

Poland sits at the intersection of Europe’s largest economic zones. From a single location, companies operating in Poland can reach markets representing over 250 million consumers within a 1,000 km radius, including Germany, France, Italy, the Nordics, and most of Central Europe.

This positioning has made Poland a natural base for:

- regional headquarters,

- shared service centers,

- technology and nearshoring operations,

- pan-European logistics and supply-chain management.

From Transit Country to Europe’s Logistics Backbone

Geographic location alone is not enough — infrastructure matters. Over the last two decades, Poland has become one of Europe’s most important logistics platforms.

According to EU transport and industry data:

- Poland operates the largest international road freight fleet in the EU,

- it is a core transit country within the TEN-T European transport corridors,

- the ports of Gdańsk and Gdynia are the largest container ports on the Baltic Sea, with direct intercontinental connections.

Logistics and transport services have evolved from support functions into key growth multipliers for the broader economy, especially e-commerce, manufacturing, and services.

A Rare European Advantage: A Truly Multi-Polar Urban Economy

Unlike many European countries, Poland’s growth has not been concentrated in a single dominant metropolis.

Instead, it developed a network of strong, complementary cities, including Warsaw, Kraków, Wrocław, the Tricity, Poznań, and Upper Silesia. This structure proved critical.

According to Oxford Economics, 10 of Europe’s 20 fastest-growing major cities between 2010 and 2025 were located in Poland — a result unmatched by any other EU country.

This distributed urban model:

- increased economic resilience,

- reduced regional inequality,

- allowed services and talent to scale nationwide.

Services as the Core Growth Engine

Poland’s geographic and urban advantages would have mattered far less without the right economic structure. The decisive factor was the rise of services, particularly technology-enabled and business services.

Today:

- services generate approximately 60% of Poland’s GDP,

- business services contribute around 5–6% of national output,

- exports of services have grown faster than goods exports over the past decade.

Oxford Economics shows that in 19 of the 20 fastest-growing European cities, business services were the first or second largest contributor to GDP growth — a pattern strongly visible in Polish cities.

Services enabled Poland to:

scale output without proportional labor-force growth,

- raise productivity despite demographic pressure,

- integrate directly into global value chains.

Productivity Over Population: A Sustainable Growth Model

A crucial insight from long-term city-level data is that Poland’s growth was driven primarily by productivity gains, not employment expansion.

This is especially important given:

- an aging population,

- declining working-age cohorts,

- limited demographic tailwinds.

Polish cities consistently outperformed European peers by improving output per worker, supported by automation, digitalization, and operational efficiency.

Poland as the Economic Anchor of Central & Eastern Europe

Poland today accounts for approximately one-third of Central & Eastern Europe’s total GDP, making it the region’s economic anchor.

Within CEE, Poland offers:

- the largest domestic market,

- the largest labor force,

- the most diversified urban network,

- the strongest position in services and exports.

For many international companies, entering Poland effectively means entering the entire CEE region.

From Catch-Up to Structural Maturity

What began as a catch-up process has now entered a new phase.

Poland is no longer closing gaps. It is defining its role among mature economies. Geography, cities, and services are no longer transition advantages — they are pillars of long-term competitiveness.

Conclusion: A Quiet Shift with Global Implications

Poland’s entry into the world’s Top 20 economies confirms a deeper shift in Europe’s economic geography.

It demonstrates that:

- long-term convergence is possible without resource dependency,

- services and technology can become national growth engines,

- Central & Eastern Europe is no longer peripheral to Europe’s future.

Poland’s rise is not an exception. It is a signal of how Europe’s economic center of gravity is steadily moving eastward.

Key Sources

IMF · World Bank · OECD · Eurostat · UNCTAD · Oxford Economics · McKinsey Global Institute